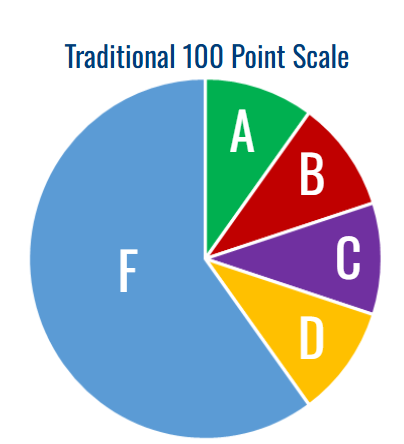

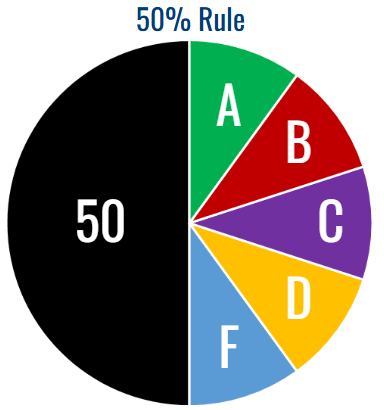

At PMHS, three core values guide grading and student success: performance, process, and progress. The grading scale is designed to reflect these principles for both parents and students. Over the years, this has been pursued through two distinct grading scales: the 50 percent rule policy and the 14-point scale.

A few years ago, issues arose with a lack of uniformity in teacher grading and the fact that Perry Townships high schools were not using the same grading scale as the rest of the district, which was the 50 percent rule policy. The 50 percent rule ensures that no student receives a grade lower than 50 percent, even if no work is turned in. “So we had a ye ar then, the first year, then we actually started working on something like this 14-point scale. Because I think from the board’s perspective, we couldn’t use the zero to 100 point scale,” Director of Secondary Education, Brian Knight said. The school board’s perspective was that an alternative was needed, one that the whole district could use. “The superintendent, and [the board] were open to listening to different ideas.”

ar then, the first year, then we actually started working on something like this 14-point scale. Because I think from the board’s perspective, we couldn’t use the zero to 100 point scale,” Director of Secondary Education, Brian Knight said. The school board’s perspective was that an alternative was needed, one that the whole district could use. “The superintendent, and [the board] were open to listening to different ideas.”

Many teachers and administrators thought the 50 percent rule, did not prove effective at the high school level. “With nothing below a 50 percent, the worry was that it would lead to increased student apathy, and in turn translate to lower test score, lower mastery, understanding, and kind of a cascading domino effect,” said Patrick Chambers, a Government teacher at PMHS. Student engagement, particularly in terms of attendance and motivation, has been a concern since COVID. Students have shown less motivation to work, and attendance rates are at an all-time low. “We exercised a great deal of grace during COVID without compromising the integrity of the content too much. I think coming off of that, when we went to the 50 percent […] we did see some apathy,” said Kert Boedicker, principal of PMHS. Knight believes that the 50 percent rule did not communicate performances clearly enough to parents. “Did they actually get 50 percent? Did they turn it in and [the teacher] just put it as a 50?” said Knight.

Some of that (the conversations) were to try and streamline some of the grading process,” Knight said. During that first year when the school started to use the 50 percent rule, various teachers, administrators and others began working on different solutions. One of the problems with the 100-point scale was the lack of consistency in how teachers applied weights in different categories. “The main purpose of a grade was to establish understanding, mastery and comprehension,” Chambers said.

This discussion was happening around the same time the board discovered that both Perry Township high schools were not adhering to the 50 percent rule. “Brian Knight, Kert Boedicker, myself and Kathy Cullison, who’s a math teacher at Southport, were kind of the core members. Then at different points in time, we would invite teachers from both high schools, and have discussions about education, ideas or thoughts or concerns that they had from every different department,” Chambers said. Their goal was to gather insights from teachers and administrators to find the best solution for students, teachers, and the overall success of the school.

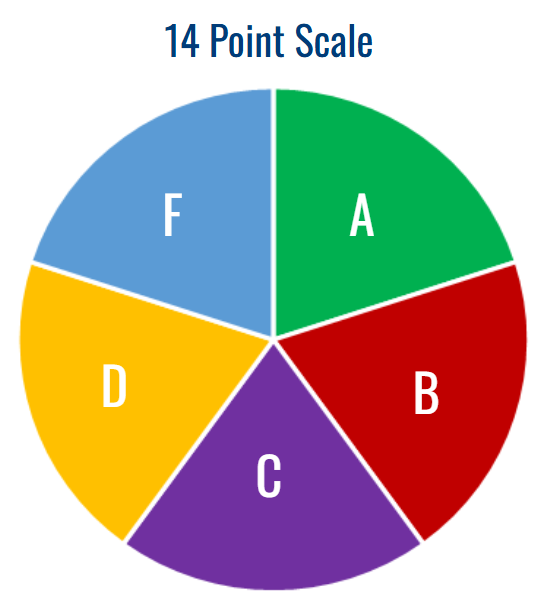

The 14-point scale, however, transforms the traditional percentage score (out of 100) into a number ranging from one to 14, with each number corresponding to a letter grade. “When we convert to scale score, the point values don’t really matter anymore,” said Knight. The percentage merely acts as a way to determine the conversion to the 14-point scale. “What we’ve tried to do in our scale was actually touch specific words with each learning level of the scale,” said Boedicker.

PMHS has been operating on the 14 point scale for about two years, and teachers are observing its impact on students’ grades. The scale was designed to reduce the weight of a zero in classrooms. “I think that people still assume that a grade represents mastery, but I don’t think that is what it shows. I see a lot of students that end up with a D or D- that have very little understanding or mastery that on the old grading scale would be in the 30 percent range and yet they’re passing because of the way this grading scale pushes people to the middle,” an anonymous Perry Township teacher said.

Teachers are noticing that some grades do not accurately reflect students’ effort and performance. Some have expressed concerns about this grading scale and its impact on their student’s grades, whether positive or negative. “At the end of the day we always tell teachers that you get to decide the final grade,” Brian Knight said. If a teacher believes a grade does not accurately reflect a student’s mastery and understanding, they can adjust it accordingly.

“The kid has a 55%, but do they really need to retake the entire semester?” Knight said. “When I was a teacher, I would ask myself—if a kid gets a D, could they have sat in the hallway all semester and gotten the same grade? And sometimes you say ‘yeah that kid kind of sat in the hallway all semester,’ and other times…there’s probably enough to move on.”

Teachers were discouraged by this response and perspective. “I feel like some people say teachers want to fail kids. […] What benefit is it for me to give a kid false hope, or to report that [students] understand something they don’t,” a Perry Township teacher said. Perry Township is committed to supporting students in reaching their full potential. However, perspectives on what achievement looks like can vary.

“I think ultimately at the high school level the biggest achievement they have is graduation. The goal is to get as many kids across that stage as we can. That changes opportunities for students having a high school diploma versus not, and that may lead to college, that may lead to workforce, apprenticeships, jobs. I think that’s the ultimate goal, especially as our population continues to change. We have more diversity and more higher needs,” Knight said.

From a teacher’s perspective, this approach can be disheartening. “I think we are pushing kids out of here with a diploma in hand, and a lot of them are going to slide because they haven’t gained either the skills or the grit necessary,” one teacher shared. At Perry, one of the school’s greatest strengths is the genuine dedication of teachers and faculty to student success. Many teachers work hard to equip students with skills that extend beyond the classroom. “If I believe in you, I am willing to put in the effort. If your inclination is to not meet my level, then I promise you that I will put in the effort to get you there,” said Tim Dye, a teacher at PMHS. “If you’re willing to put in the effort. I don’t need the 14 point scale to get you there. I am willing to work with you to help find success.”

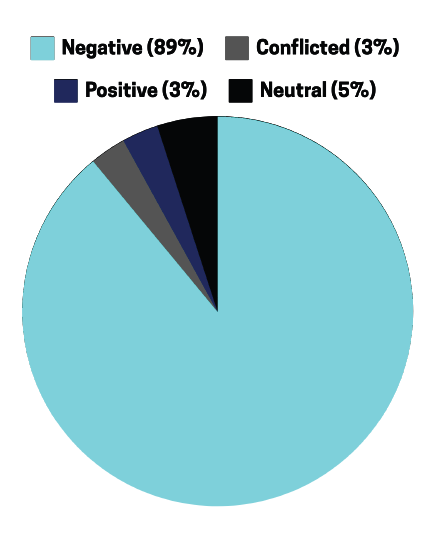

The graph above shows PMHS faculty responses to a confidential FOCUS poll asking for opinions on the 14 Point Scale.

The ultimate goal at Perry, as Boedicker explained, is ensuring that students acquire essential, transferable skills. “So wherever the next step is for that student, they take what they have learned here, and then they become successful in whatever endeavor.” In Perry Township, grades are meant to accurately reflect a student’s work and effort. “We had agreed that a grade should represent a combination of mastery, progress and growth, skill attainment and achievement,” Chambers said. These principles were outlined in a document that the grading committee had put together as an alternative to both existing grading scales, intending to present it to the board.

A student reporter had the opportunity to review this document, which included standardized grading practices designed to support students while maintaining their accountability and engagement in the learning process. “No one grade would devastate a semester grade,” a Perry Township teacher noted. Despite concerns from teachers and board members about inconsistencies in grading, the proposed solution was ultimately rejected by the board. Instead, they pushed for a 12-point grading scale at the township level, which was an earlier draft of the 14 point scale. It was used at Southport for one year. Some parents at Southport expressed concerns and attempted to engage in discussions with administration, but instead of getting rid of the 12-point scale altogether the 14-point scale became the result.

Admin uses this example of a student’s possible report card to demonstrate how the 14 Point Scale converts to the traditional 100 point scale.

When considering the grading system, Knight and others had to navigate multiple layers of concerns, particularly around grade inflation. “Then you get into [how] this over-inflated a kid’s grade, and now they’re moving on. Did a kid on the 100-point scale have the right knowledge to move on either? No. That’s not a kid who is magically going to get into an Ivy League school now because this scale is inflated. Look at outcomes of learning rather than the math problem of the kid’s grade. I think they (teachers) are only focused on the math of it. I don’t care what we use. There’s going to be an issue with it,” Knight said.

“It pushes kids along. We can say we have an x percentage rate in graduates, but I think the quality of the students we are putting out is a lot lower. The number of times I hear students say, ‘I want to get into this school, honors college, early admission. My GPA is fine, but I don’t have the standardized test score,’” a Perry Township teacher said .

There is significant pressure at the board level to maintain a high graduation rate, as it directly impacts funding. However, when the focus shifts primarily to numbers, it raises an important question—at what cost? This concern has led many to reflect on the values of the education system and the long-term implications for future generations.