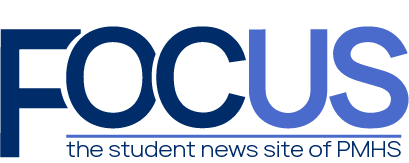

Remember the email sent by administration describing yet another change with the way our

grading system works? It is here after Perry Township Schools replaced its 14-point grading

scale with a system more modeled after the previous one. Reverting back to the majority of a

grade, 80%, comes from performance tasks like tests, labs, and projects, and just 20% comes

from basic practice work. The shift is set to change how teachers teach, how students study and

how grades tell the story of learning.

English department head Jessica Hunter called her first reaction “a jubilant celebration of

excitement” over returning to a traditional grading scale, which she thinks better shows student

growth and learning. Believing the change will help students track their progress more clearly,

especially high-achieving students who struggled to maintain top grades under the 14-point

system. “I think that the traditional grading scale is more equitable and accurate in measuring

student growth and learning,” Hunter said, “Isn’t that what a grading scale should be?”

The district aims to balance encouraging student effort and maintaining high academic

standards. Claiming that the changes are designed to provide more accurate and meaningful

feedback about academic progress in each content area. Prior, a retake policy was set by each

teacher, but now, according to an informational pamphlet handed out by the district, students will

be able to retake any performance assignment or make-up with a corrective assessment,

regardless of grade. To qualify, students first have to make a valid attempt at the assignment. To

most teachers, this means meeting the basic requirements and showing a genuine effort.

Hunter made it clear, “The corrective assessment for essays is the process,” Hunter said. The

assessment is built into the process, from prewriting to multiple drafts, so by the time a final

paper is submitted, it should be a student’s best work. “If a student has not worked through the

process and just threw a paper together, I’d challenge them to look at the district policy saying

there must’ve been a valid attempt,” Hunter said. The ongoing challenge, she added, will be

keeping students motivated throughout the process.

Scott Simmonds, science department chair, welcomed the end of the 14-point system. He felt

that it made it too easy for students to pass without putting in real effort, while also making it

harder for top students to earn an A. He views the new scale as a middle ground that

challenges students.

Simmonds expects fewer, more meaningful performance assignments, with larger, point-based

practice assignments playing a bigger role. In his classes, smaller assignments act as building

blocks for bigger projects, meaning skipping them can hurt overall performance. To keep

students engaged, Simmonds plans to expand project-based learning and labs, such as biology

projects where students create “macro meal” recipe cards that combine nutrition with

biochemistry concepts.

Social studies department chair Nathan Orme believes the updated scale will be easier for

students, teachers and parents to comprehend. “The old system confused students who

struggled to see how individual assignments impacted their final score,” Orme said, “The new

system gives teachers more control to support students through weighted assignments and

tailored opportunities for improvement.” The social studies department will continue to meet and

discuss strategies for handling essays and DBQs.

Students who excel on projects and tests may see higher grades under the new system, while

those who rely on homework to boost scores could face challenges. The 80/20 split adds

pressure on big assignments and requires studying. Reassessment opportunities could be a

safety net for some, but minimal effort won’t be a valid attempt.

As the first quarter meets the halfway mark, teachers and students will be learning the ins and

outs of the new grading system. Whether it improves grades or creates new challenges, this

year’s grades will be done in a very different way from the previous year.